Roger Penrose's AI skepticism

Despite recent advances in Artificial Intelligence, I sometimes encounter the claim that while computers can do many tasks well, human-level AI is not possible for fundamental reasons. Skeptics claim that computers can never be as smart, creative, generally intelligent as humans.

Accomplished mathematician and physicist Roger Penrose has been very outspoken about his AI skepticism. I once had the priviledge of attending a talk he gave on the subject. Here is a presentation he gave in 2020 with a very similar structure.

Penrose believes that humans can do something no classical computer can do, i.e. compute non-computable functions. In other words, he thinks we can solve problems no Turing machine can solve. This implies no standard computer can solve them, and not even quantum computers can solve them. The advantage of quantum computers is that they can solve some problems faster, but in principle they too can be simulated on Turing machines.

One has to admire the fact that he realizes, and goes along with, the full implications of this view.

If we believe standard neuroscience, human thoughts are encoded in the strength of interactions between neurons, which act as summing and thresholding devices. In other words, our brains are a kind of deep-learning neural network. Neural networks however obviously can be simulated by classical computers. So if we believe Penrose’s arguments, this implies that neuroscience is completely wrong about this.

He understands this very well, and thus, together with Stuart Hameroff, has developed an alternative hypothesis of how human thinking works. It has to do with supposed quantum entanglements between microtubules in our brain cells.

But that’s not enough: even quantum physics can be simulated on classical computers. Thus Penrose goes further, and posits a whole new physical hypothesis, Orchestrated Objective Reduction, that adds a non-computational component to quantum physics that somehow our thoughts must be tapping into.

In the first 25 minutes of the talk he discusses evidence that how human brains supposedly exhibit non-computational elements that cannot be simulated by computers. This is what I will address. I do not find any of these arguments convincing.

The remainder of the talk discusses the hypotheses for new physics and new neuroscience that would explain non-computability, which I am not going to attempt to discuss.

Computer chess

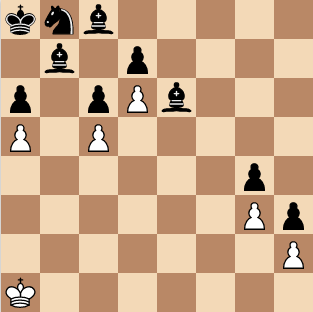

At 2:40 of the presentation he discusses a chess position.

Humans chess players quickly realize that the position is a draw. All white has to do is move the king around on black squares, and black can’t make progress.

Computer programs don’t immediately realize this. They think black has a massive advantage.

Penrose cites “Fritz at grandmaster level” as the computer program. The same is true for Stockfish. It takes Stockfish a long time to realize it’s a draw.

If you don’t give Stockfish a very long time to think, it is likely to blunder by giving up its free bishop in order to avoid a draw, thinking it still has a big advantage, but in fact this will allow white to win.

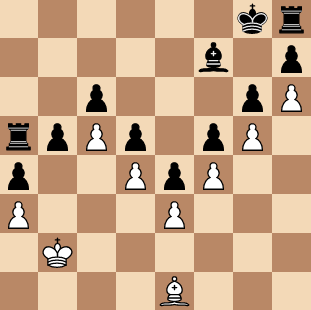

In other talks, Penrose has shown other similar positions.

Humans quickly find the drawing move: Bb4. After that just move the king around and black will never get through the wall.

Stockfish takes a very long time to find this move, and even longer to realize it is a draw.

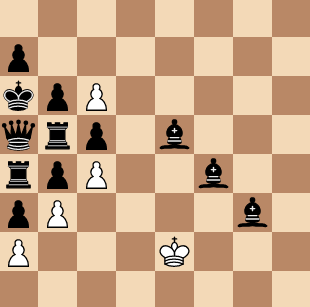

Stockfish thinks white is losing badly. Humans quickly realize that white can just move the king around on white squares and never move the pawns, and the black pieces are forever trapped, resulting in a draw.

Penrose claims these examples demonstrate that humans have something no computer can ever have. But do they really?

No, they don’t. What they do show is that Fritz and Stockfish have still not reached the human level at chess for these particular weird situations. Humans still have a better algorithm than these computer chess programs, for these positions. It does not mean that no computer program ever will be able catch up and understand these positions quickly just as humans can.

Fritz and Stockfish are chess programs that perform a game tree search and evaluate positions using a hand-coded evaluation function. All these examples have the same pattern in common. They have a bunch of pieces forever trapped behind their own pawns. Apparently it’s not a pattern that the programmers of Fritz and Stockfish have implemented in their programs. They could implement this sort of topological reasoning, but they have decided not to. It’s a lot of work to implement, and the situation occurs rarely in games, so they didn’t bother. Maybe they will in a future version of Stockfish. Or maybe some other computer program, like a future version of AlphaZero, will be able to figure this out by itself.

50 years ago computers were worse at chess than human amateurs. Some people were claiming it would be very hard or impossible for computers to beat humans. 20 years ago the same was true of go. Many people claimed that go was the kind of game that was inherently very hard for computers and it was either impossible for computers to beat humans, or that it would take centuries of AI research. Now computers are better than humans in the vast majority of chess and go situations, but we can still construct some exceptional positions that computers analyze worse than humans. Penrose is repeating the same mistake as chess skeptics made 50 years ago when he suggests that these positions are inherently hard for any possible computer chess program.

The point that Penrose is making is that these computer chess programs do not exhibit the kind of general pattern-recognition and intelligence that humans possess. That is true. Of course they don’t. Yet. Nobody claims that Fritz or Stockfish has achieved general AI. They haven’t. This doesn’t demonstrate that general AI can’t ever be achieved.

The argument from Gödel’s first incompletness theorem

At 8:27, Penrose switches to his main argument from mathematical logic. He says “this is the key to what I want to say”.

In the past many people have criticized this argument, and Penrose has responded with various variants of the argument, some of them more complicated than others. All of them are faulty in various ways. In trying to fix one problem somebody has pointed out, he introduces other problems.

Nevertheless, in this talk, he returned to the most basic version of the argument, which is great, because it is also the one that makes it easiest to see where the mistake lies.

Here is the argument as presented in his slide:

Turing’s version of Gödel’s theorem tells us that, for any set of mechanical theorem-proving rules R, we can construct a mathematical statement G(R) which, if we believe in the validity of R, we must accept as true; yet G(R) cannot be proved using R alone.

He then goes on to say that this shows we humans can do something the theorem-proving machine cannot do.

There should immediately be something fishy about this. We listen to a quick one-slide argument and that already shows we’re smarter than any future AI? That’s not even the height of our potential as humans! Surely a robot could grasp the gist of the argument he’s making! But let’s not be so quick to dismiss.

First a couple quick comments.

When he says “Gödel’s theorem”, he refers to Gödel first incompleteness theorem. There are a few other famous and relevant Gödel’s theorems: Gödel completeness theorem, and Gödel second incompleteness theorem, but it’s clear he’s talking about the first one.

I am a bit confused about the “Turing’s version of” Gödel’s theorem. I don’t know what that is. There is a proof of Gödel’s incompleteness theorem that uses Turing machines, but then it’s still the same theorem. There is also a different argument that Penrose has used in the past that uses the Halting Problem rather than Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, which Turing proved to be non-computable. But the Halting Problem doesn’t refer to mathematical proofs in a formal system of logic. So I’m just going to assume we’re talking about the actual Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem, which is consistent with the rest of the slide and what Penrose says about it.

When talking about subtle theorems in mathematical logic, one has to be very careful and precise. It’s easy to fall into contradictions and paradoxes if one is not careful.

To make the concepts of “theorem proving” and “mathematical statements” precise, let’s be specific here. There is no 100% unanomous agreement as to what the foundations of mathematics really are, but the most standard approach that most mathematicians are fine with is to take axioms of set theory and rules of first order logic as the foundation of mathematics. Specifically, most mathematicians tend to assume Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory, abbreviated as ZFC, as the foundations of mathematics. Let’s go with that. I have certainly never seen a mathematical proof that couldn’t be formalized in ZFC. So I think it’s a pretty good definition of what we mean today when we say “a mathematical proof”.

So let’s take R = ZFC in Penrose’s slide. The theorem proving rules are certainly mechanical. We can indeed write an algorithm that will enumarate all proofs that follow from ZFC axioms. Gödel’s incompleteness theorem then implies that there is a certain statement, G(ZFC) that, if ZFC is consistent, then it has no mathematical proof. It also implies that if ZFC is consistent then G(ZFC) is true.

Seems almost like a contradiction, which is why we have to very careful and precise.

When Penrose’s slide says “if we believe in the validity of R”, what he really means is that R (i.e. ZFC) is consistent (or a stronger property such as arithmetic soundness, which in turn implies consistency). We write that as Cons(ZFC). Statement “X is provable in ZFC” is usually written as . So what we get from Gödel’s theorem are the following two statements:

The first statement says that if ZFC is consistent, then there is no proof of G(ZFC). The second statement says that if ZFC is consistent, then G(ZFC) is true.

Penrose’s argument starts with: we believe ZFC is consistent, otherwise it would make no sense to use this as a foundation of mathematics. Let’s grant that this is something we believe in.

As a side note: the history of set theory is that we first had a set of axioms, so called “naive set theory”, that later turned out to be inconsistent. ZFC is our latest iteration at formalizing mathematics. We hope that this time there are no more inconsistencies. We have been using it for a while and nobody has found any contradictions. If there is a contradiction lurking, a lot of time invested into developing set theory will have been wasted. So hopefully it is indeed consistent this time.

But it’s not really 100% certain, we don’t have a proof of this. In fact, Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem says we can’t have a proof of this if it’s true, at least as long as ZFC remains our foundation of mathematics.

But let’s grant that we believe this to be true. So the argument goes: given that we believe Cons(ZFC) to be true, the first statement says that the theorem-proving machine can never prove G(ZFC). The second statement says that G(ZFC) is true.

And that’s it. We know something the machine doesn’t!

But wait a second. We asked the machine to prove things to us mathematically! Did we prove mathematically that G(ZFC) is true? No we didn’t! There is a big difference between the following two statements:

We proved the first one. We didn’t prove the second one! We may believe that the second one is true based on our belief in Cons(ZFC). A belief is very different from a mathematical proof however!

The theorem-proving machine cannot produce a mathematical proof of G(ZFC), and neither can humans.

The theorem-proving machine can produce a mathematical proof of the first statement (Gödel’s theorem), and so can humans. That’s what Gödel did. The machine produces all possible proofs, so it will also produce the proof that Gödel found.

So in the end this doesn’t demonstrate any difference between the machine’s and humans’ abilities to produce mathematical proofs.

What about beliefs? We may believe G(ZFC). The theorem-proving machine will never state a belief in G(ZFC). Does it mean we are smarter than machines?

No, the machine doesn’t state a belief in G(ZFC) because we’re not asking the machine to tell us about its beliefs. It’s a theorem-proving machine, not a theorem-believing machine, by assumption. We are asking it to produce proofs. The assumption of the whole argument was that the machine produces formal proofs of mathematical statements, not that it tells us its beliefs without proof.

Stating a belief in G(ZFC) is not non-computable. I can easily write a Python program that can do the same trick that Penrose does and state its belief in G(ZFC):

print('I am 100% convinced that G(ZFC) is true.')

The fact that Roger Penrose states this belief without proof is thus not evidence of his brain’s non-computable abilities.

Plane tilings

At 14:45, having finished the argument from Gödel’s theorem, the talk switches to the example of tiling the plane with polyominoes.

The question of whether a given set of polyominoes can be used to tile the plane is a non-computable problem. There is no computer algorithm that, given a set of polyominoes, decides whether it is possible to fully tile the plane using them.

Penrose then presents a set of 3 polyominoes that can be used to tile the whole plane, but in a non-trivial way. It’s an example of a so called “Penrose tiling”, Penrose having done a lot of study of this kind of tilings.

The suggestion here seems to be this is an example of something Penrose can do which computers cannot do. But again this argument doesn’t work!

What the cited theorem implies is that there are some sets of polyominoes that computers can’t figure out. It doesn’t mean that this particular 3-polyomino set is one of them. There is also no reason to think that Penrose could figure this out for every set of polyominos, demonstrating his non-computable ability.

As Penrose says later in the talk, this 3-polyomino set tiling actually works according to a regular pattern. It’s just that it’s not the most trivial, translationally-symmetric pattern. It is possible to write a computer program to search through such patterns and eventually find this one that works.

He also states that the brute force algorithm would be really slow for this when trying to cover even a finite area with these tiles. OK, but the brute force algorithm is not the only possible algorithm! A better computer program could do what Penrose did, look for patterns, and find the one that works.

Goodstein’s theorem

At 18:30 he switches to Goodstein’s theorem. It is a theorem about natural numbers. It has been shown that it doesn’t follow from Peano’s Arithmetic axioms (which he calls “ordinary induction”), but it does follow from set theory (ZFC) axioms.

It is an interesting fact, but honestly I don’t understand the relevance of this. Neither humans nor computers can prove it from Peano’s Arithmetic axioms since it simply doesn’t follow from them. Both humans and computers can prove the theorem from ZFC axioms of set theory, since it does follow from them.

Conclusion

General human-level AI is in our future. None of Penrose’s arguments do anything to convince me that humans have abilities that computers can’t have. Recent advances in deep learning continuously shrink the set of abilities that are unique to humans, and the trend will continue.