How to pick a hash function, part 1

See also part 2.

- Summary

- Hash tables

- Ad-hoc hash functions are bad

- Obfuscated hash functions: not a real solution

- Utopia

- Universal hashing

- Hashing an integer

- Hashing bigger data

- Hashing variable-length data

Summary

If you don’t read the rest of the article, it can be summarized as:

- Use universal hashing. It is simple, efficient, and provably generates minimal collisions in expectation regardless of your data.

- Most hash table implementations don’t do this, unfortunately. Standard libraries of common programming languages don’t do this. Instead, they use inferior ad-hoc functions. That creates problems.

Note: This article only talks about hash functions for use in hash tables. Hash functions for use in cryptographic applications are a very different topic that we don’t cover here.

Hash tables

A hash table is a great data structure for unordered sets of data. Whenever you have a set of values where you want to be able to look up arbitrary elements quickly, a hash table is a good default data structure.

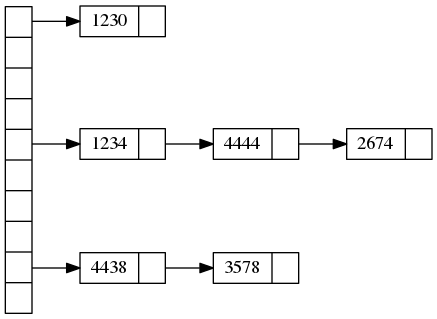

It typically looks something like this:

On the left we have buckets. Each bucket contains a pointer to a linked list of data elements.

We also need a hash function that maps data elements to buckets.

In the above example we have 10 buckets, data elements are numbers, and the hash function is the last digit of a number: , .

To find an element, we first compute the hash function, and then scan the list in the appropriate bucket. This is quick as long as we don’t have too many elements in the bucket.

The worry is: what if the hash function is not well-suited for our data and most elements end up in the same bucket? Then the access time will be bad.

For instance, if the keys are prices of products in a grocery store, then most prices will end with the digits .00 or .99. If we use the last two digits as the hash function, we would store everything in two buckets. This wouldn’t work well!

This is the reason many programmers are afraid of using hash tables. Is my hash function good for the data? Should I switch to the newest and fanciest hash function that somebody has recently published? How do I test it with my data?

I will argue that with appropriate implementation, these are non-issues. We will see that a hash table should really be a randomized data structure. If we do this correctly (and it’s not hard to do), the performance will be good in expectation regardless of the data.

Unfortunately, common libraries do not do this correctly (yet).

Ad-hoc hash functions are bad

Let’s solve the following artificial problem in a brute force way using hash tables:

Given and , compute:

There are better ways to solve the problem but we just want to use a hash table as an experiment.

OK, let’s write some C++ code.

std::unordered_set<long> generate(long A, long B) {

std::unordered_set<long> data;

for (long i=1; i<=A; ++i) data.insert(i * B);

return data;

}

long sum(const std::unordered_set<long> &data) {

long res = 0;

for (long x : data) res += x;

return res;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

long A = std::atoi(argv[1]);

long B = std::atoi(argv[2]);

auto data = generate(A, B);

std::cout << sum(data) << "\n";

}

And run it:

$ time ./hashing 1000000 123

61500061500000

real 0m0.135s

user 0m0.119s

sys 0m0.016s

$ time ./hashing 1000000 3141592

1570797570796000000

real 0m0.153s

user 0m0.136s

sys 0m0.017s

$ time ./hashing 1000000 1056323

^C

real 1m10.137s

user 1m10.107s

sys 0m0.024s

In the fist two cases we get an answer in 0.15 seconds. In the last case, A=1000000, B=1056323, we never got an answer. I just killed the program after a minute. If would take about 45 minutes to complete.

It’s not that we were extremely unlucky. This will happen every time we run with these inputs. If you want to know the answer for A=1000000, B=1056323 you have no choice but to wait for 45 minutes! (Or you modify the program, but that’s not the point.)

Well this is ridiculous. We just want to add a million numbers. It shouldn’t be that hard.

I’m sure the readers already suspect what the issue is. Hash table collisions!

It turns out that my implementation of the C++ standard library uses 1056323 buckets for a hash table of size 1000000, and the hash function it uses is simply . Since our numbers are all divisible by 1056323, everything ends up in bucket 0.

Obfuscated hash functions: not a real solution

A solution many people use in practice is to, instead of a simple ad-hoc hash function like , use a much more complicated ad-hoc function, with a lot of arbitrary arithmetic instructions thrown together: shift bits around, add things together, multiply things, xor things, etc etc.

Examples of this are: MurmurHash, FNV Hash, PJW Hash, Jenkins Hash, Spooky Hash, etc etc. People come up with them all the time.

There isn’t really any secret sauce behind these functions. Various authors simply pick an arbitrary sequence of arithmetic operations to make the function more complicated.

This doesn’t really solve the underlying problem. What it does is sweep the problem under the rug. Because the functions are so complicated, it is much less obvious what kind of data is bad data. It is also less likely your data will accidentally happen to be worst case data.

But it’s not guaranteed. It could just so happen that your type of data interacts with one of these hash functions in a bad way.

Perhaps more importantly, it is very easy to deliberately search for and find bad data. This leads to a denial of service attack against your program. If, for example, you’re running a website and the backend of your website uses a hash table, an evil user can deliberately send you data that will cause your server to run very long computations due to hash collisions.

Utopia

What if we use a random function as the hash function? Just pick any function randomly out of the space of all possible functions.

It looks like this would work. Let’s say you have elements in the hash table, . Let’s also assume we’re looking up an element that does not exist in the table (worst case scenario for lookup). The expected number of elemements in the same bucket as is:

Therefore the expected lookup time would be .

As long as we have enough buckets with , lookup time is , i.e. constant time in expectation.

Great! Can’t get any better than that.

There is a problem with this solution however. There are a lot of possible hash functions! If there are possible keys, there are possible hash functions.

Just to store a description of randomly chosen hash function, we need at least bits. In other words, we would need to store a huge array of hash values, one entry for each possible key. But if we do that, then we could just as well not use a hash table at all, and just store the set elements directly in that array! The whole purpose of having a hash table is to avoid having an array with one entry for each possible key.

So this doesn’t work. But there is a better way.

Universal hashing

The idea behind universal hashing is similar to the the idea behind Utopia. We will still choose a random hash function. But we limit the set of possible hash functions, so that we can store it compactly in very small amount of memory.

The only property of random hash functions that we really needed in the Utopia proof was: for two different keys and :

It would also be OK to have a slightly larger bound, say .

Fortunately, this is achievable! If a family of hash functions satisfies this property, we call it a “universal family of hash functions”, and call a randomly chosen function from that family a “universal hash function”.

Hashing an integer

If your keys are integers in some range, do this:

- Pick a prime number that is at least as large as the range of keys.

- Pick random , .

The Carter-Wegman hash function is:

This is a universal hash function. .

Proof sketch. For a given pair of keys, , is not divisible by , because are all smaller than . Therefore . For a random choice of the pair is in fact a uniformly random pair of non-equal numbers modulo . There are such pairs, and less than of them match modulo . Therefore collision probability is less than .

So, just use this function and you’ll be fine!

One possible complaint might be that this function involves two expensive modulo operations. However both of them can be avoided:

- If you choose to be a power of 2, then mod m is just a cheap bitmask of the lowest bits.

- If is a compile-time constant, then there is a way to compute mod p using multiplication instead of division. The idea is to multiply by a precomputed fixed-precision approximation to instead of dividing by . Good compilers do this automatically.

- If is a Mersenne prime, mod p can be computed even easier using just bitshifts and addition. Again, good compilers do this automatically.

See also part 2 for even better hash functions.

Hashing bigger data

Suppose we have a data structure consisting not of just one number , but of numbers .

In that case we randomly select multipliers , and use:

This guarantees collision probability of at most for different keys, by a very similar proof. It’s sufficient that at least of the is different.

Hashing variable-length data

Suppose that we have variable length data , so is not a constant. We only have some large limit on the length.

In this case what we can do is:

- Pick a prime number .

- Pick a random number

- Pick a random hash function for single integers in range 0 to .

The hash function for variable length data is:

Inside the parentheses we are evaluating a polynomial of degree at most modulo at a random point .

If we have two different variable-length keys and , then we are evaluating two different polynomials at the same random point. The difference between polynomials is itself a polynomial. A polynomial of degree at most can have at most roots. Therefore the probability that the two polynomials give the same value at is at most .

If the two polynomials are different at , then we’re applying to two different integers. In this case we know the probability of collision is at most .

Therefore the total collision probability is:

This is good enough to get expected access time to the hash table.